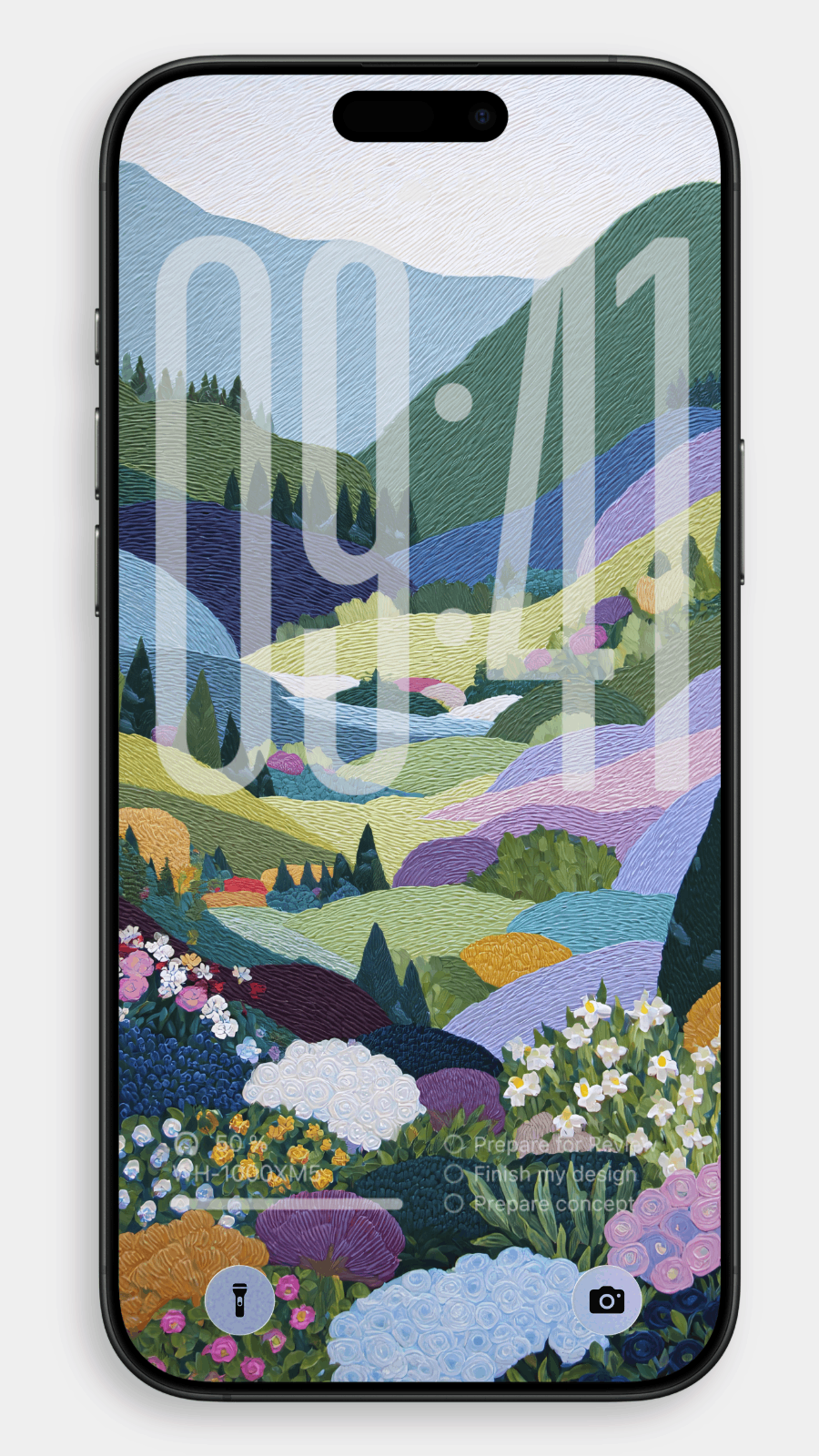

Upgrade your screen with a perfect blend of tradition and modern minimalism. Above the Mountains, inspired by Wu Guanzhong’s iconic vision of a “Thousand-Mile Landscape,” brings elegant Chinese aesthetics to your iPhone or Android in stunning 8K clarity. These iOS 26-ready phone wallpapers fuse classic ink-brush serenity with sleek, contemporary design — ideal for fans of minimal style and timeless art. Picture mountain ridges fading into mist, delicate strokes that whisper of distant peaks, and tranquil tones that let your app icons breathe. Whether you’re a design lover, art enthusiast, or just someone who wants a phone background that feels peaceful and intentional, this collection hits the sweet spot. The wallpapers are optimized for both iOS and Android devices, ensuring your screen stays sharp and stylish. Tap into a digital scroll painting every time you unlock your phone — a pocket-sized gallery of serenity and story.

You can download all these wallpapers on Dejavu Wallpaper!

Experience the magic of AI in advance! Let the infinite imagination of AI decorate your screens, bring you fresh delights every day.

Have you ever stood atop a mountain, gazing into the horizon where one ridge folds into another? It feels like the patterned ink of a Chinese painting—or perhaps an unspoken poem from someone’s heart. Wu Guanzhong, the master who merged ink painting with modern composition, once transformed these layered landscapes into dreamlike spaces with his brush.

A Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains—Not Just Wang Ximeng

When we mention “A Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains,” most think of the iconic blue-green scroll painted by the Song dynasty prodigy Wang Ximeng. But in the late 20th century, Wu Guanzhong reimagined his own vision of that legacy. His was not a revival of traditional green mineral pigments, but a fresh, breathing visual rhythm: dots, lines, and planes dancing across the canvas. His mountains didn’t merely stack—they pulsed like a symphony, or hummed like a folk song.

In this new visual language, we see the spirit of a “post-thousand-mile” landscape: soft greens meet purples and blues in gentle transitions, and the mountain forms build momentum without ever becoming heavy. That sense of weightless layering is signature Wu Guanzhong—balancing abstraction and emptiness to turn nature into a realm of memory and emotion.

Where Does a Mountain’s Rhythm Come From?

Wu once said, “Art is not an imitation of nature—it is the distillation of its spirit.” In these works, the mountain shapes are not topographically accurate, but they possess a musical rhythm—like a crescendo followed by a hush. During his studies in France, Wu was deeply influenced by modernist art, drawn especially to the lines of Picasso and Matisse.

Yet Wu did not become a Western painter. He brought those techniques home, constructing mountains from points and lines, using minimalist composition to conjure vastness, and always retaining the vital “qi” (spirit) of Chinese ink painting. There’s no ink wash here, but you can feel the flow of water and the breath of mountains.

Hidden Secrets in the Mountains

What’s lesser known is that Wu often didn’t paint directly from life. After years in Yunnan, Guizhou, and the Jiangnan region, he compiled these landscapes from memory—blending, reshaping, reconstructing. His “mental landscapes” sometimes resemble Huizhou, sometimes Zhangjiajie, sometimes his hometown of Yixing.

Within them lie quiet surprises: a lone willow tree nestled in the foreground, or a sudden shift from gray to violet breaking the flow. These details are not mistakes—they’re like a bird’s call echoing through the valley, or a sigh hidden in brushstrokes.

From Wu Guanzhong to the AI Age of Landscapes

Today, digital visuals—whether on Midjourney or wallpaper apps—regularly echo the “layered mountain” motif. But the ones that carry Wu Guanzhong’s spirit are quieter, constructed from points and planes, and full of that distinctly Eastern sense of poetic emptiness.

These are the new thousand-mile landscapes. No longer confined to scrolls or museum walls, they flow across screens, whispering the same question: how do we keep dreaming of mountains in the modern world?

Wu Guanzhong once said, “Art is a lonely road.” But the mountains he left behind still accompany us through the noise of today. In those endless greens and quiet contours, we don’t just see peaks—we glimpse a nation’s lasting longing for beauty.